Category: Race and Religion

-

Making Sense of the Moment We’re In

Run It Black Podcast · Making Sense of the Moment We’re in 2020 has been a year unlike any for most of us. From coronavirus to the national movement against police violence, it feels like we’re in a moment that could best be described as tectonic. This week on the…

-

Feel the Bern and Vote for These Philly Judges on Tuesday, May 21

Bernie Sanders wants you to vote for good Philly judges on May 21. Hannah Spielberg recommends Kyriakakis (19), Palmer (23), and Yu (27).

-

We Miss the Old Kanye…

Kanye West is oft considered one of the greatest musical talents of his generation. He also supports Trump and recently gave an interview stating his belief that slavery was a choice. This week on the show, David and Mike dive down the rabbit hole that is Kanye West’s mind, explore…

-

The Nation of Islam Problem

The Nation of Islam is officially recognized as a national hate group due to its black supremacist, anti-Semitic and anti-LGBTQ views. And yet, Tamika Mallory, a prominent black activist and national co-president of the Women’s March, attended one of their biggest annual events anyways. This week on the show, David…

-

The World of Wakanda

This week on the show, David and Mike travel to Wakanda to dissect the latest blockbuster installation in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, the Black Panther. The Run It Black hosts cover topics of Pan-Africanism, white supremacy and identity in this hour-long episode. Even if you haven’t seen the movie yet,…

-

Neoliberalism, Meet Neocolonialism.

Neoliberalism. What is it? Why should we care? And how has our popularly held notions of the rise and spread of neoliberalism shaped contemporary conversations on issues of race, class and progress? This week on the show Mike and David sit down with Professor N.D.B. Connolly to discuss his recent…

-

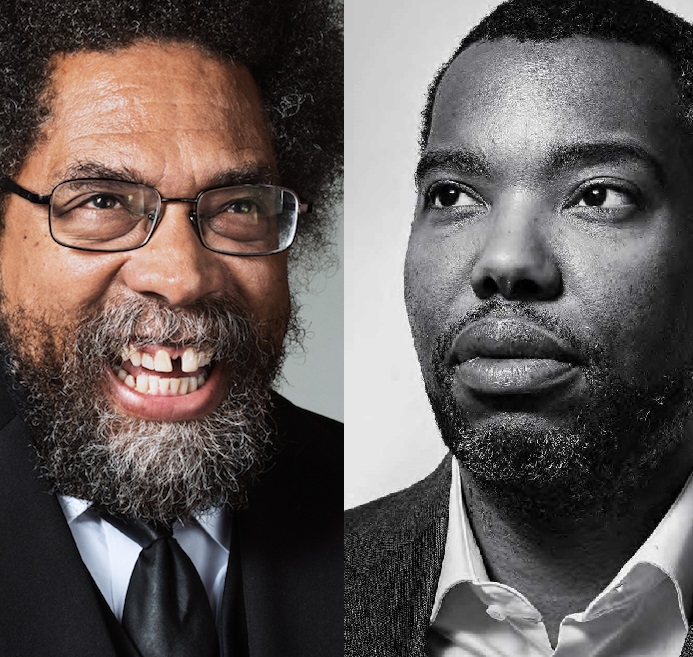

Ta-Nehisi Coates, Cornel West, and the Ongoing Debate on Race and Class

This week on Run it Black, Mike and David talk about the latest entry into the ongoing intellectual debate between philosopher and activist Cornel West and critically acclaimed essayist Ta-Nehisi Coates. The conversation covers a range of topics including identity politics and the Obama administration, the roles of race and…

-

Andre 3000 Still Got Something to Say

Andre 3000 is one of our favorite rappers of all time. We talk about his continual relevance as well as the evolution of Hip-Hop.

-

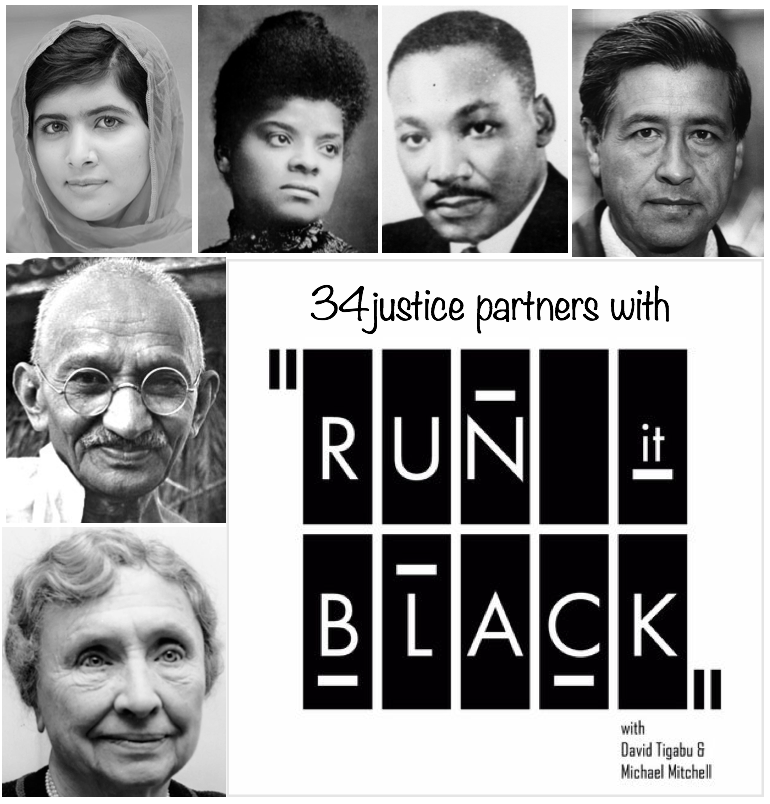

34justice Partners with Run It Black

I’m excited to announce that 34justice is partnering with Run It Black, a podcast on “sports, politics, culture, and the intersection of race” from David Tigabu and Mike Mitchell. Mike taught me much of what I know about podcasting, and David is no newcomer to 34justice, having previously authored a great piece for…

-

Black Death as Spectacle and Ritual

A black person does not really discuss black people dying without also feeling a subtle contempt or masochism, but there is also gratitude when black death is made public (à la Mamie Till, Emmett Till’s mother, insisting for the world to see what America did to her son by having an…