Category: Poverty and the Justice System

-

How District Attorneys Can Promote Justice and Increase Public Safety

Restorative approaches to criminal prosecution and holding the powerful accountable easily beat harsh punishments for drug-related crime.

-

Resident Perspective: It Begins

This is the continuation of a series of journal entries depicting what it’s like to be a part of the COVID pandemic from the medicine resident perspective. Wednesday, March 25th Today was my first day of quarantine and now I feel like I’m a part of society. In the prior…

-

Governor Wolf and the Courts Must Act Now to Mitigate Public Health Threat

Jails and prisons pose a greater public safety risk than any individual they cage, especially during a pandemic.

-

On Both Politics and Policy, “For All” Beats “For Some”

We have the money to enact universal programs, which are more efficient and effective than their means-tested counterparts.

-

Feel the Bern and Vote for These Philly Judges on Tuesday, May 21

Bernie Sanders wants you to vote for good Philly judges on May 21. Hannah Spielberg recommends Kyriakakis (19), Palmer (23), and Yu (27).

-

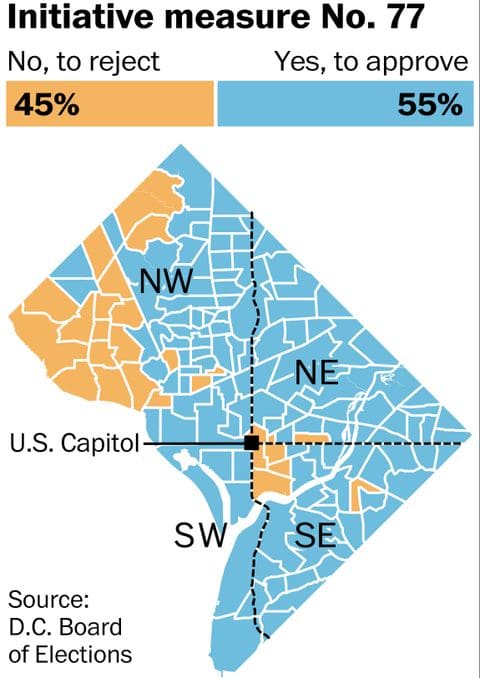

Dear Councilman Grosso: Please Be Our Ally and Support 77

Being an ally to women and immigrants, which you’ve been in the past, means raising wages for vulnerable workers.

-

Listen to Tipped Workers

The voices of the low-wage majority of tipped workers have been underrepresented in the debate over DC’s Initiative 77. Their stories must be heard.

-

Written in 2017, Relevant in 2018 and Beyond

GOP lies, Democrats’ illiberalism, media failures, what good policy looks like, and how to win

-

How to Spin an Agenda for the Rich as an Agenda for the Poor, by Paul Ryan

If you back my agenda, you may get asked about its immorality during the tax debate. Here’s my guide on what to say.

-

34justice Partners with Run It Black

I’m excited to announce that 34justice is partnering with Run It Black, a podcast on “sports, politics, culture, and the intersection of race” from David Tigabu and Mike Mitchell. Mike taught me much of what I know about podcasting, and David is no newcomer to 34justice, having previously authored a great piece for…