Category: Philosophy

-

How Accusations of “Negativity” and “Divisiveness” Stifle Debate

Candidate records & platforms matter. As can be seen in the race for DC State Board of Education in Ward 1, it’s important to point them out.

-

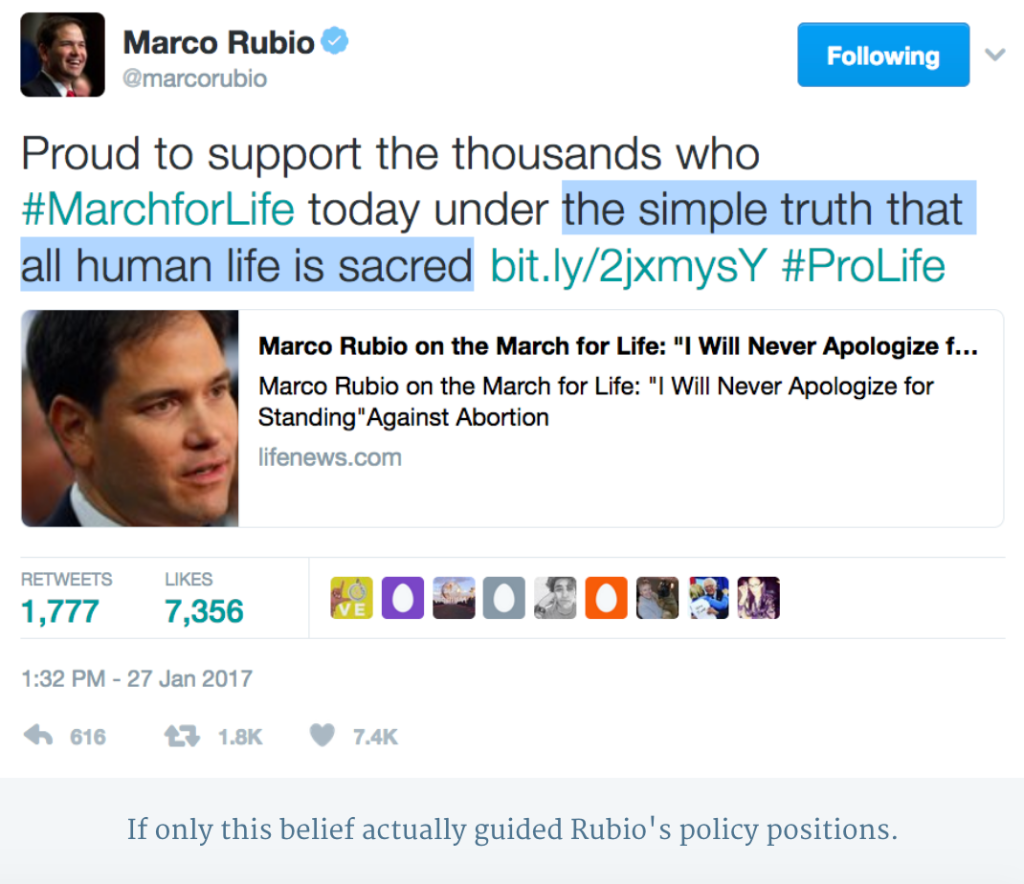

“March for Life” and “Pro-Life” Are Misnomers

If you’re not anti-war, anti-death penalty, pro-inclusive immigration, and pro-substantial benefits for the poor, you’re not “pro-life.”

-

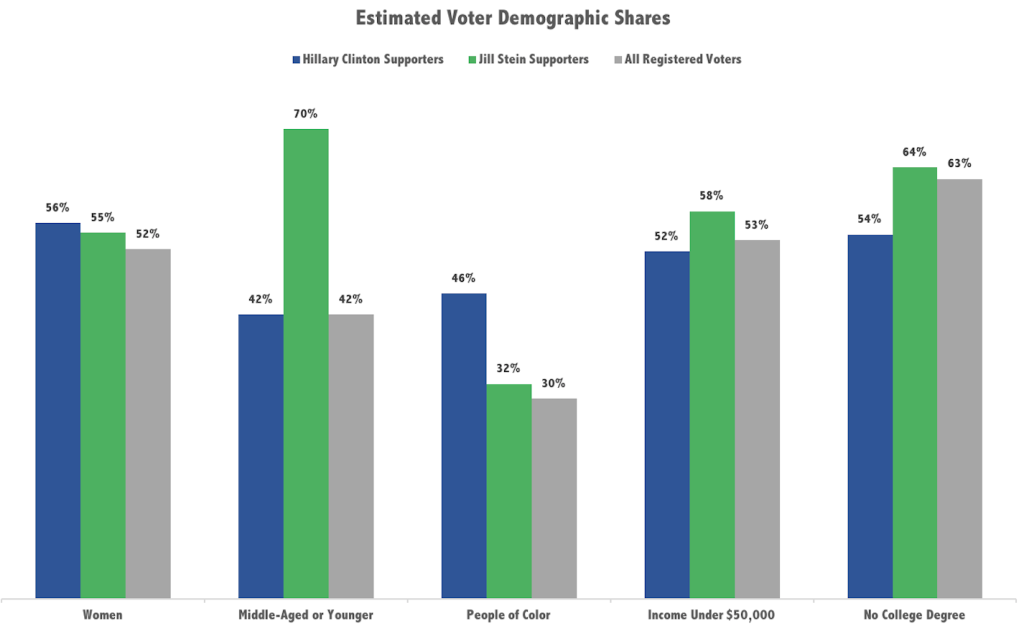

Privilege: Many Jill Stein Voters Have It, and Many Hillary Clinton Voters Do, Too

As an outspoken supporter of Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein, I often get questions akin to the one Stein was asked at the Green Town Hall on August 17: “Given the way our political system works, effectively you could help Donald Trump like Ralph Nader helped George Bush in…

-

Truth or Politics

Tom Block is an author, artist, and activist whose most recent book, Machiavelli in America, explores the influence of the 16th-century Italian political philosopher on America’s politics. Machiavelli’s impact is particularly apparent today, as Block explains in the post below. Block (who you can follow on Twitter at @tomblock06 and…

-

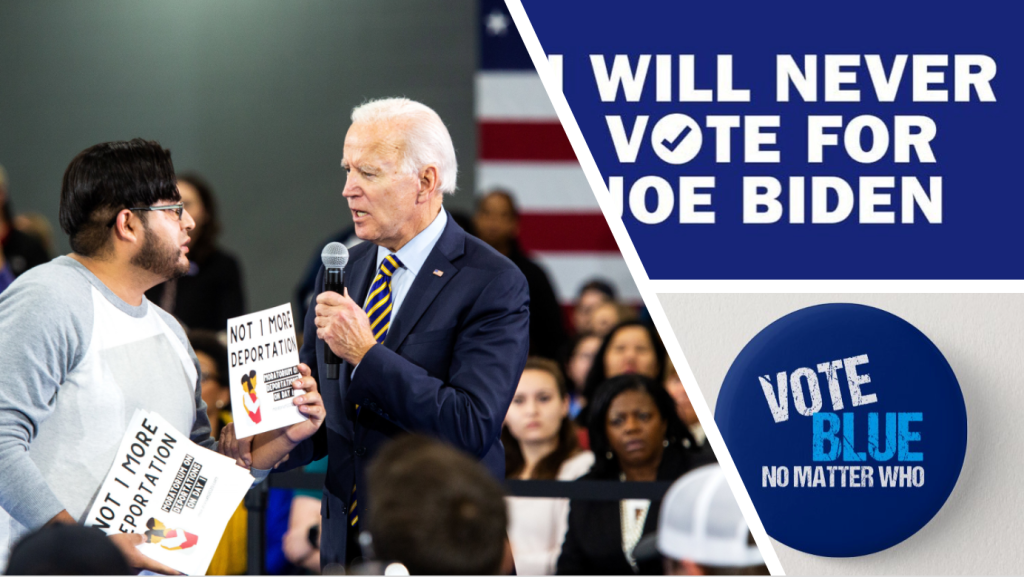

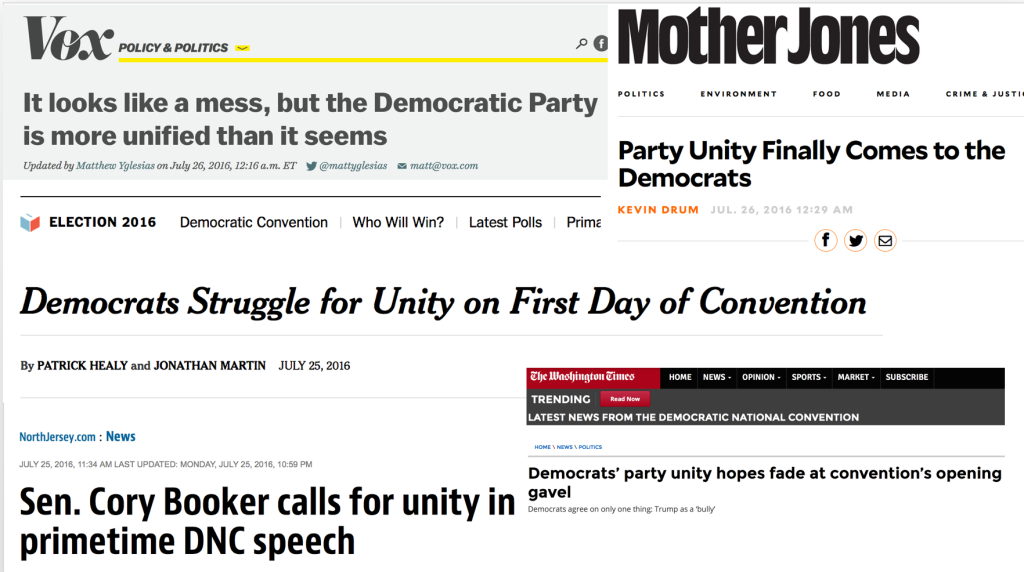

What Unity Should Mean

If headlines about the Democratic convention (shown below) are any indication, the main purpose of the event is “party unity.” Calls to “Unite Blue” have been intensifying as the Democratic primary process has inched towards a close and represent a pitch for Bernie Sanders supporters to rally around Hillary Clinton,…

-

What’s the Best Way to Deal with the Ku Klux Klan?

On the recommendation of my friend and colleague Mike Mitchell, I recently listened to a fascinating podcast about Daryl Davis, an award-winning musician who is best known for his role in bringing down the Maryland chapter of the Ku Klux Klan – through his friendship with Klan members. In the…

-

A Response to Machiavelli: Three Legislative Proposals

Tom Block is an author, playwright and artist. In his last 34justice guest post, Tom described Niccolò Machiavelli’s influence on American politics. He also laid out his proposal for a “Moral Ombudsman,” a nonprofit that would “offer a true moral center from which to judge the legislation and actions of”…

-

Machiavelli in America and One Response to this Social Illness

Tom Block is an author, playwright and artist, whose work spans more than two decades. In this blog post, Tom introduces us to his political antidote to our Machiavellian political sphere. Adapted from his book, Machiavelli in America, this piece is part of Tom’s greater exploration of how to bring…

-

The Political Lens: What Global Warming and Wright v. New York Have in Common

During the 2003-2004 school year, my chemistry teacher told my class that global warming wasn’t occurring. I believed her. When I attended New Jersey’s Governor’s School of International Studies in the summer of 2005, a professor told me the opposite – the evidence for global warming, and for the human…