I once began a K-12 education talk by putting the following two questions on a screen.

1. What is the single policy change that would most improve the quality of K-12 education?

2. What is the single policy change that would most reduce the opportunity gap between low-income and high-income students?

I asked audience members to, by a show of hands, indicate which question spoke to them more. They had three choices:

A) Question 1

B) Question 2

C) Doesn’t matter, since both question 1 and question 2 have the same answer

Stop and think for a second about which choice would have prompted you to raise your hand.

If you would have selected choice C, you would have been joined by about 90 percent of the audience at my talk. I expected that result. In a culture in which politicians routinely say things like “education is the closest thing to magic we have here in America” and cite low graduation rates in low-income areas as evidence of our education system’s failures, that view is unsurprising.

It’s also completely wrong. The overwhelming evidence that choice C is incorrect falls into at least five primary buckets:

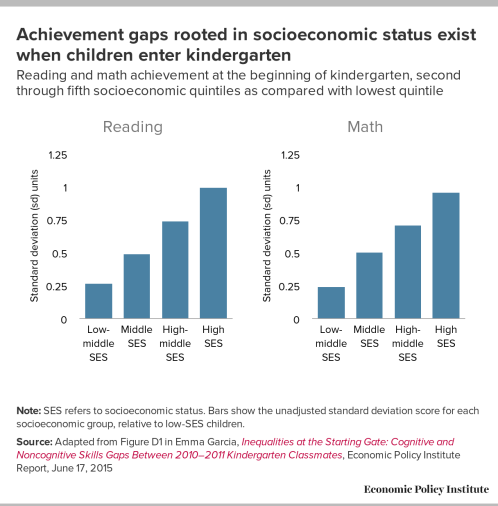

1) There are large gaps in test score performance in the United States before students enter kindergarten. The graph shown below, from the Economic Policy Institute, documents the extent of these gaps (there are gaps in various cognitive and noncognitive skills as well), and as Sean Reardon has shown, there is evidence that they close during the school year, only to reopen during the summer months. The gaps have declined in size since the late 1990s, but they are, in Reardon’s words, “still huge.”

Inequitable access to preschool for low-income students is definitely part of the problem here, but gaps are apparent in infancy and probably due mostly to differences in housing, nutrition, medical care, exposure to environmental hazards, stress, and various other factors.

2) Decades of research into the causes of the gap in test scores between low-income and high-income students in the United States has consistently found a limited contribution from school-based factors. In the US, variations in school quality seem to explain no more than 33% of the discrepancies in test score performance; this number, which has been around since 1966, considers the influence of a student’s classmates to be a school-based factor (it arguably isn’t) and thus seems to be a conservative upper bound. Most studies put the school-based contribution to what is commonly called the “achievement gap” closer to 20%, with about 60% attributable to “student and family background characteristics [which] likely pertain to income/poverty” and the other 20% unexplained.

3) Economic success in this country is less common for low-income students who are successful in school than for high-income students who are unsuccessful in school. The graph below, made using data from the Pew Economic Mobility Project, compares the distribution of adult economic outcomes for children born into different quintiles of the income distribution with different levels of educational attainment. If education were the prime determinant of opportunity, we’d expect educational attainment to determine these adult economic outcomes. Yet the data show that children born into the top twenty percent who fail to graduate college typically fare better economically than children born into the bottom twenty percent who earn their college degrees. In fact, the born-into-privilege non-graduates are 2.5 times as likely to end up in the top twenty percent as adults as are the born-poor college graduates.

4) The test scores of students in the United States relative to the test scores of students around the world aren’t all that different than what students’ self-reports of their socioeconomic status would predict. The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) has an “index of economic, social, and cultural status” which incorporates family wealth, parents’ educational attainment, and more. There is a gap in test score performance between students who score high on this index and students who score relatively low on it in every country in the world. The size of the gap varies by country, as does the median test score, but there is a strong correlation overall between students’ socioeconomic status and their performance on standardized tests. The first graph below, in which each data point relates the average socioeconomic index score for a decile of a particular OECD country’s students to that decile’s average performance on PISA’s math test, depicts this relationship.

As the next two graphs show, test score performance for the bottom socioeconomic decile in the United States falls right on the OECD bottom-decile trend line, and while U.S. test scores for the second decile are a little below the OECD trend (as are U.S. scores for the next few deciles), socioeconomic status seems to explain American students’ performance on international tests pretty well overall.

5) The distribution of educational attainment in the United States has improved significantly over the past twenty-five years without significantly improving students’ eventual economic outcomes. While people with more education tend to have lower poverty rates than people with less education, giving people more education neither creates quality jobs nor eliminates bad ones, as Matt Bruenig has explained. A more educated population (see the first graph below), therefore, just tends to shift the education levels required by certain jobs upwards: jobs that used to require only a high school degree might now require a college degree, for example. The “cruel game of musical chairs in the U.S. labor market” (as Marshall Steinbaum and Austin Clemens have called it) that results is likely part of why poverty rates at every level of educational attainment increased between 1991 and 2014, as shown in the second graph below.

Bruenig’s analysis lacks a counterfactual – the overall poverty rate may well have increased if educational attainment hadn’t improved, rather than staying constant – but it’s a clear illustration of the problem with primarily education-focused anti-poverty initiatives.

None of this evidence changes the fact that education is very important. It just underscores that direct efforts to reduce poverty and inequality – efforts that put more money in the pockets of low-income people and provide them with important benefits like health care – are most important if our goal is to boost opportunities for low-income students.

Leave a comment